Below the streets lies an underground city of the dead, a place where practical solutions met eerie beauty. I explore how the paris catacombs were born in the late 18th century when officials moved remains from overcrowded graveyards into abandoned quarries.

The transfers were driven by health fears and the need to protect the living. Over six million people were moved and their bones arranged into the solemn walls visitors see today. Those arrangements created a quiet, ordered space that feels unlike the city above.

I’ll separate fact from folklore, including the Paris catacombs mystery that draws curious travelers from around the world. Expect clear explanations of why the ossuary exists, what the official route covers, and why much of the underground maze remains off-limits for safety and conservation.

Key Takeaways

- Origin: The ossuary began as a public-health solution in the 1700s.

- Scale: More than six million remains and walls of bones line the tunnels.

- Reality vs. legend: Many eerie stories stem from the setting, not proven events.

- Access: The official route is small; hundreds of miles remain closed to visitors.

- Why it matters: It shows how a city manages its past beneath everyday life.

Beneath the City of Light: What lies under the streets of Paris

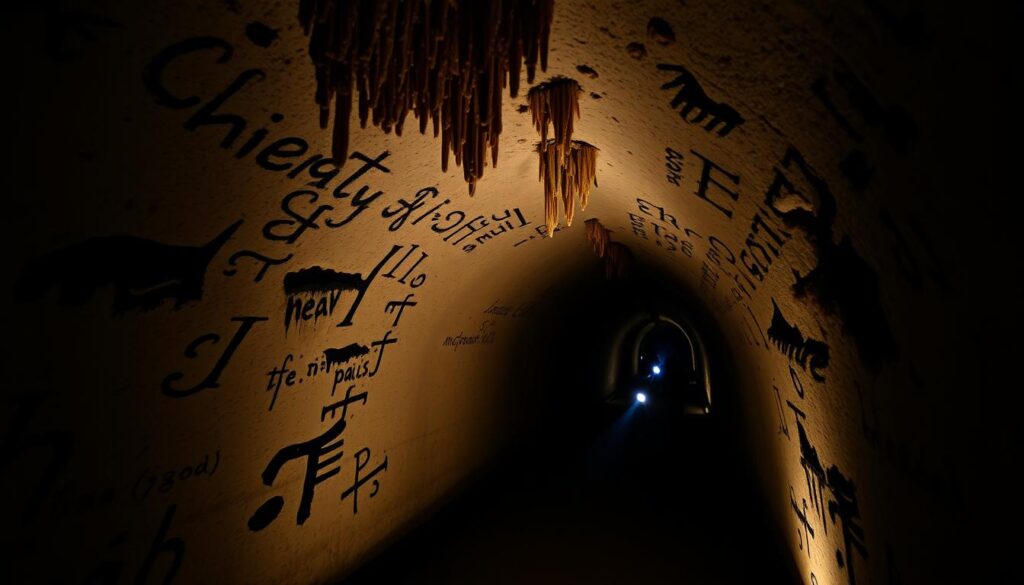

Hidden under the urban surface, long quarry galleries form a subterranean place of memory that links geology with human history. The network sits below the modern city, carved from limestone and later repurposed as an ossuary.

The official route leads visitors under the streets paris into long corridors. These managed sections show patterned walls of bones and skulls arranged to steady the tunnels and honor the dead. The layout follows old quarry paths that once supplied stone to buildings above.

The feeling down here is intense: the darkness, the cooled air, and the echo of footsteps. That hush makes the space feel like a city basement—necessary and structured, yet off-limits in many areas for safety and preservation.

- Walk below the streets and notice the temperature drop and the quarry-cut corridors.

- Only a reinforced museum path is open; vast tunnels remain closed for protection.

- The narrow passages, stacked remains, and silent air create an experience unlike anything above ground.

From crisis to solution: The 18th-century origins of the ossuary

By the late 18th century the growing city faced an urgent sanitation challenge. Inner burial grounds overflowed and daily life rubbed up against open graves.

Holy Innocents’ was the largest, taking roughly a tenth of deaths each year. It sat beside the Les Halles market, so decomposing matter mixed with market waste. Contemporary writers warned of “cadaverous miasmas” as a dangerous air that harmed residents.

Overcrowded burial grounds and public health alarms

The crowding made a clear public health problem. In 1765 the Parlement banned church burials inside the limits, shifting burials to sites outside the walls. That law aimed to protect people even as it challenged custom.

When Holy Innocents’ closed and exhumations began

In spring 1780 gases from graves broke into cellars and sickened neighbors. Authorities issued a royal order to close the cemetery. By December 1785 night transfers began: bodies were quietly moved underground as a practical solution.

| Year | Event | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1765 | Parlement forbids church burials inside city | Shift of interments outside city limits |

| 1780 | Gases breach cellars near Holy Innocents’ | Closure ordered; residents ill from foul airs |

| 1785 | Night exhumations and transfers begin | Start of organized relocation underground |

Quarries, sinkholes, and the making of safety underground

A sudden sinkhole on Rue de l’Enfer turned hidden quarry risks into an urgent public crisis. In 1774 the collapse swallowed houses, carts, and people, dropping them more than 84 feet. That dramatic event made the danger visible across the streets and stirred widespread panic.

Officials moved quickly. In 1777 Louis XVI created the Inspection Générale des Carrières (IGC) to survey and secure the underground. Chief Inspector Charles‑Axel Guillaumot led the effort, mapping galleries and shoring weak sections.

Rue de l’Enfer collapses and the panic that followed

The collapse showed that the forgotten quarries threatened life above ground. Citizens demanded action. Workmen and engineers began shoring tunnels to stop further failures.

The IGC and Guillaumot: mapping, shoring, and maintaining the mines

Guillaumot’s team drew precise plans of the underground. They reinforced galleries and created a system to monitor the old mine works. Over the next few years, these measures stabilized large areas beneath the city.

- Engineering first: shoring stopped sudden drops and made rebuilding possible.

- Administrative rise: the IGC became the long‑term guardian of the subterranean network.

- New purpose: stabilized quarry spaces later offered a practical solution for housing millions of remains.

The story here shows how practical engineering solved an immediate safety problem. That same groundwork shaped how the underground was used and remembered as the centuries moved on.

Building the Empire of the Dead: how six million human remains found a place

Nightfall set the scene: carts rolled quietly, torchlight flickered, and workers moved the city’s displaced dead with care. Exhumations began in December 1785 and continued through the winter months to limit public disturbance.

On April 7, 1786, officials consecrated the Paris Municipal Ossuary, formalizing a process that mixed ritual and civic need. During the Revolution and the Reign of Terror, burials increased and the site took on the identity of an empire dead.

How the underground took shape

The presentation below ground became deliberate. Workers arranged skulls and long bones into patterned walls. That design stabilized galleries and created a sober visual language.

- Imagine torchlit carts and careful transfers—logistics and respect together.

- Consecration in 1786 gave the site civic and spiritual legitimacy.

- The Revolution accelerated interments until the site held roughly six million remains.

That chapter of history, rooted in the 18th century, shows how a practical solution became a lasting, solemn landmark. For visitors today, the arranged bones are a reminder of how a city keeps its past beneath the streets.

Unraveling the Paris catacombs mystery: history, tunnels, and whispers of the dead

A hush settles in the tunnels, and ordinary sounds turn strange and small. That quiet fuels the many stories people pass along after a visit.

Whispering walls, sudden chills, and shadowy shapes are common reports from visitors and urban explorers. In low light, footsteps echo and the brain fills gaps with meaning.

Whispering walls, sudden chills, and shadowy figures

In the darkness, many say they hear soft voices or feel watched. These sensations often reflect fatigue, low light, and the mind’s urge to explain unknown sounds.

Philibert Apsairt and the doorman’s ghost

The story of Philibert Apsairt mixes record and legend. A doorman vanished and a body, later identified by a ring, was found years after. Folks now claim his spirit appears each November 3.

The lost camcorder legend and vanishing explorers

One widely told tale describes a found camcorder with frantic footage that ends abruptly. The alleged disappearance inspired films and kept the catacombs in the public imagination.

Secret rooms, alchemists, and guardian spirits: myths that endure

Rumors of hidden chambers, alchemists’ labs, and guardian figures add layers to the lore. Hard evidence is thin, yet the sheer volume of accounts keeps these stories alive.

- The atmosphere feeds imagination: in low light, small noises become dramatic.

- Philibert’s tale blends verifiable fact with folklore.

- The lost-camera story shows why this place fascinates the world: fear of getting lost taps into deep worries about death and confinement.

From forbidden areas to tourist attraction: explorers, visitors, and the world below today

The underground today balances careful access with vast, forbidden zones that lure adventurous explorers. The official museum route is small, lit, and monitored. It is the part most visitors see and it functions as a managed tourist attraction.

Beyond that rope lies roughly 200 miles of closed galleries. Those unauthorized areas attract urban explorers but are dangerous without training. Officials warn that identical corridors and low light can quickly disorient anyone off the marked path.

Safety, access, and what to expect

Stay on the signed route. In one documented case, teenagers were lost for three days before sniffer dogs found them. That rescue shows why the site enforces limits.

- The museum path is stabilized and monitored for visitors.

- Unauthorized tunnels span miles and are illegal to enter.

- Expect cool air, dim light, and views of arranged bones—powerful but safe if you follow staff directions.

For most tourist-minded people, the official trail offers a full, respectful experience of the site. If you do venture into exploration subcultures, do so with training and permission. Otherwise, enjoy the history and let professionals protect the rest of the underground city.

Conclusion

An urgent public-health fix in the 18th century turned unsafe quarries and overcrowded cemeteries into a managed place for human remains. The paris catacombs hold the remains of millions in ordered walls that reflect a city solving a problem over many years.

Walk the route and you meet history, skulls, and the quiet weight of six million people. Legends and stories grew around the tunnels, but the core fact remains: this was a practical response to danger and decay.

Practical note: stick to the authorized path, respect guides, and give yourself time to absorb the experience. The catacombs remain a powerful tourist attraction that links infrastructure, memory, and the lives of past people.